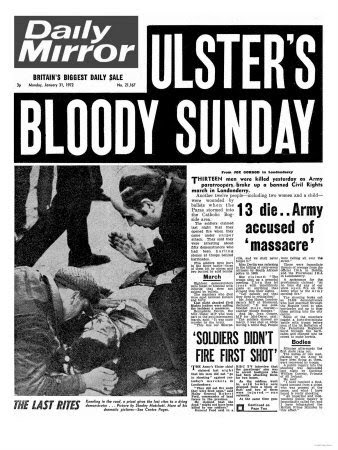

Bloody Sunday occurred on January 30, 1972. The Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association (NICRA) planned a peaceful protest. The anti-internment marches took place in the city of Derry. In response, the Unionist community, led by Ian Paisley, mobilized to hold a counter protest. The British government sensed that a dangerous confrontation was likely to ensue and drafted its elite paratrooper regiment to deal with the unfolding scenario. Although the Unionist counter march was called off, the anti-internment march went ahead. The protestors began in Creggan estate and the route would take them through the Bogside, to Derry city center.

Before the protest, tensions were already high from previous IRA and British soldier skirmishes. “For this particular day, however, the two IRA movements stated that they would refrain from hostile activity.” (Maurice Punch). The British government was still leery about the protestors because of past violent protests. The British officials were on guard because of constant IRA nail bombings and guerrilla warfare tactics in Northern Ireland. Though IRA members stated that the protest would be peaceful, the British did not want to take any chances.

The Irish Nationalist claim that the British paratroopers lacked discipline, intentionally killing innocent victims. Though the official British report claimed that the paratroopers were innocent, Irish campaigns for disseminating official documents began. Post-colonial Ireland is subjugated to British control of the media, government, and political structure. The British government was accused of falsifying documents and withholding information from the public. For years, the Irish nationalist could not get a fair trial on the event and families of the fallen protestors demanded answers.

The British nationalists or “Unionists” claim that the British paratroopers were fired upon and were defending themselves from violent protestors. “Bloody Sunday is also a ‘contested past’, since the soldiers were exonerated of any wrong-doing at the Public Inquiry set up by the British Government to investigate the killings in their immediate aftermath, conducted by the Lord Chief Justice, Lord Widgery” (Graham Dawson). In the final official report, the British soldiers were innocent and not convicted. The past occurrences with IRA nail bombings, fire fights, and violent protests supported the British Unionist’s agreement with the paratrooper’s actions. The British government claimed that the rebel groups were terrorist and a threat to public safety.

Public history is important in the British and Irish conflict because memory is our social “tool-kit”. How humans have defined their cultural identity, is through their past histories. Public perception of Bloody Sunday is constantly evolving. Identity is created through religion, gender, and ethnicity. The past events literally makeup who an individual is, and could be both negative or positive. “In the case of Northern Ireland, the identity category of Protestant was historically ranked above Catholic and this became the basis for the way the state acted toward and treated the Catholic population. Thus the subordinate position of Catholics became normalized in the Northern Ireland state.” (Conoway Brian)

The dichotomy of the two cultures in Ireland, being Catholic and Protestant, created social friction. The “us” vs. “them” mentality has been a public history staple in every conflict. And one way groups delineate themselves from other groups is through historical events. Remembering the past is important in Bloody Sunday, because civil discourse is still present globally. The act of protestors being killed is not unique to Bloody Sunday. Remembering the events that took place may help future governments and protesters from violence.

The events in the “Troubles”, including Bloody Sunday, eventually led to peace agreement treaties. “The result was the Downing Street Declaration in 1993. By then, the beginnings of what came to be known as the ‘peace process’ was under way, leading to the Loyalist and Republican cease-fires of August 1994.” (Marie-Therese Fay, Mike Morrissey and Marie Smyth) The peace negotiations eventually led to the “Good Friday Agreement”, and the IRA announced that their military tactics would end. The tragedies and casualties during the turbulent time period have come to a stop. But the violence that proceeded the Good Friday agreement were deemed necessary by the Irish nationalist.

“Not every Nationalist or Unionist in Northern Ireland took part in the events of Bloody Sunday. Not every Nationalist or Unionist was a witness to it either. Many people, both Nationalist and Loyalist, re-member that day as a watershed moment even though they were not there in person. Whether they saw the events on television or mediated through others byword of mouth, they remembered Bloody Sunday as participants in a community of memory.” (Conoway Brian) Though the events have different perspectives and understandings, the event itself is an important part of both the Irish and British collective history. The event itself is a clash of two radically different ideologies and motivations, but are cemented together through collective identity.

Sadly, the years that followed Bloody Sunday (1973 to 1993) were filled wit instability and civil unrest. Like the majority of conflicts, hindsight makes one look back and think that the devastation was unnecessary. The multiple Irish nationalist parties and British Unionist parties fought for political support. The opposing sides and cultures seemed doomed to never come to a political agreement. The years of instability eventually led way to political progress and reform.

The Irish Troubled have claimed many lives, imprisoned, and separated families. The results of the conflict can be tangible through monuments, memorials, and tributes. The principle lessons that can be learned from these events will always be present to the Irish and British. The events in some ways can offer a hopeful message that one day peaceful agreements can be reached. The majority of the Irish state just wants to leave peacefully, as most people in the world do. But violence is sometimes the gears to enact permanent change.

In conclusion, the “Troubles” in Northern Ireland, has a long and complex history, dating back before the “Bloody Sunday” or “Bogside Massacre” incident. The facts of the event are concrete, however, the details of the event are bias depending on varying political views. The affair is recorded and passed down to future generations, through popular culture and the media. The event led to the “Good Friday” peace agreement. And the tensions between the opposing factions still remain high. The tragedy of the event, as well as lives lost, will go down in historical infamy.

Michael Guerrero

References

Lord Widgery and Samuel Dash. 1972. “Bloody Sunday”. International Journal of Politics. Vol. 10: No. 1. pp: 46-58.

Brian Conway. 2003. Active Remembering, Selective Forgetting, and Collective Identity: The Case of Bloody Sunday. An International Journal of Theory and Research. Vol. 3: No. 4. pp: 305-322.

Maurice Punch. 2012. State Violence, Collusion and the Troubles. London: Pluto Press. Pp: 1-28.

Graham Dawson. 2005. Trauma, Place and the Politics of Memory: Bloody Sunday, Derry, 1972-2004. History Workshop Journal. Vol. 1 No. 59. pp: 151-178.

Marie-Therese Fay, Mike Morrissey, and Marie Smyth. 1999. Northern Ireland’s Troubles. London: Pluto Press. pp: 51-72.