A Visual Analysis of British Imperial Propaganda (c. 19th & 20th century)

Narrative and Imperial Rule

Media and culture are mainstays in the imagination of any governing imperial force: In the case of imperial Britain, propaganda worked as a megaphone by which the parliament in place was able to communicate and shape the narrative(s) of their colonial agenda abroad. In this way both the national and commonwealth public was shown a carefully constructed narrative of the benefit, benevolence, and burden of Empire. And although this was not always intended to be a deception, various outlets of British media (most famously and widely read was The Times, of London) dramatically simplified a very complex international situation of violent nationalism and opposition. It was in fact through these same simplifications that a more tolerable narrative was constructed: In which, Britain was simply actuating what Rudyard Kipling had so wonderfully coined, “The White Man’s Burden.”

- The English saw themselves as members of an ordered society

- The world should strive to emulate their order and escape the brutality and violence of savagery (a lack of whiteness often equated this sub-cultured status of being)

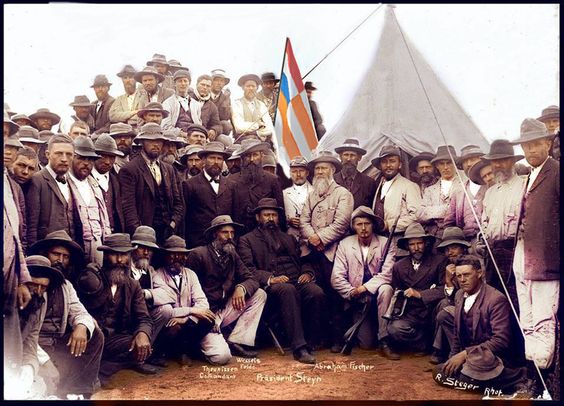

By the beginning of the twentieth century, British media had mastered the art of “structuring” commonwealth happenings in a manner that made otherwise radical information highly palatable to the Anglo-Englishman. Notions of nationalist fervor were rarely mentioned; thus, such outlets sought to portray event(s) like the Anglo-Boer War of 1899 – 1901 or the Indian call for Home Rule (actualized in 1947) as products of successful and well-intentioned English/Anglo civilizing. In fact, according to the British imperial imagination, citizens of India and other indigenous would seek independence as a natural byproduct (Darwinian in form) of their own education.

A beacon of civilization, the English were to lead the various non-Anglo races, walking hand-in-hand into a brighter future in the same way a child follows their parents down an uneasy road. This is, of course, the perception of any true Englishman: A white man’s burden to enlighten and lead. The reality of such situations may be far different than that reported in an imperial newspaper via image or story.

The Social Implications of Public History & Media

The endeavor at hand delves into communication as a feature of imperial maintenance. Without an appropriate structuring of information the public would have very little understanding of the state-of-empire: How is Australia faring in the Pacific or in what way has South Africa been cast into political dissension? It was a time of reading and seeing. Furthermore, this collection and display has aimed to enliven an understanding (or at least further existing public knowledge) on the many features of Britain as a colonial entity and its legacy within the media.

Media, in this case, can include literature, academic text-books, films, newspapers, etc. and unequivocally sought to conform with the imperial policy of its day.

For example, when it came to establishing India and various categories of Indian, Muslim, and later Pakistani individuals within the British imperial imagination newspapers were crucial tools used to garner support for national policies and actions abroad. Often the British depicted non-white persons as inferior — this is exemplified by the British press’ depiction of Indians as savages during the Indian Mutiny. (Parsons, 46) The sensationalized narratives spun by such newspapers about the course of events (including the failure to justify actions taken during the Anglo-Boer conflict) served many purposes including a racially charged and perturbing understanding that “civilizing the lower casts” was the real intention behind maintaining control throughout the world.

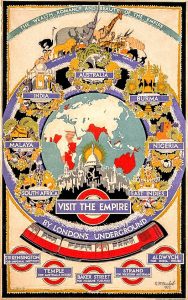

News media (as a British institution) saw the city of London as both their imperial capital and the center of empire: A hub wherein all other corners of the world felt connected and wherein the established rules of civility could be witnessed via their purest form. A strong physical allusion of cultural supremacy, the cityscape was riddled with posters and flyers that evoked a mighty “civilizing” construct. This position as a focal point of authority undoubtedly lead to an elevation of British cultural superiority amidst the global community.

To be British in this way would encompass all cultures and so the Empire itself became a social experience. For this reason (and many more) there had been no need for the hierarchy of British authority to travel throughout their own Empire and so the majority of their racially motivated decision-making became inspired almost exclusively from historical texts or social theory.

The imperial “image” of London can be viewed as an allusion to nationalism itself in dialogue with urban space(s). Furthermore, public history has commonly been denoted as a diverse and accessible process by which the past can be incorporated into the world today. Truly this form of history calls for a bridge between the otherwise academic or political spaces in the world, challenging the general public to join in the discourse.

David Gilber alongside Felix Drive have examined this phenomenon in their work Capital and Empire: Geographies of Imperial London, suggesting: “In 1932, for example, posters by the designer Ernest Dinkel invited Londoners and tourists to take a tour of the ‘wealth, romance and beauty of the Empire. All that was needed was an Underground ticket: Australia could be reached via temple, India via Aldwych, and much of the rest of empire via South Kensington.”

Distance is therefore no longer a factor in the Imperial imagination. What is foreign does not determine difference, for London embodies all cultures, and so the perception of early-twentieth century imperialists was (interestingly) influenced almost exclusively from reading and literature. Indeed, seeing was an important component within this paradigm, but what Londoners “saw” had been photographs of elephants, aboriginal people in vast tribes, the “uncivilized” parts of the world. In this way reading from papers and seeing from pictures became ways to justify the civilizing mission: Looking up from a newspaper, the imperial British person would see the miracles of a modern, urban society. Tilting their head back down, however, they would return to a world of chaos, featuring an Anglo-Boer conflict and unclothed Indian/Muslim nationalists calling for independence.

Whether it be through exhibition, library, or more immediately, via the media, such history inevitably echoes from age to age – sometimes changing over time, and other times remaining the same – the historian, therefore, is not its only purveyor. A newspaper editor or writer is very much a participant in this conversation between the everyday persona and the parliament laying down the law. This is not to say that English officials were at a point writing the news themselves, though it is very clear that upon the arrival of industry and call to divvy up Continents such as Africa, the media served as a wonderful outlet to establish civilizing missionary tactic and justify the abroad endeavor as righteous, divinely inspired, and even gracious.

The Boer War & an Imperial Approach to Media

Literature has often been considered a tool for nostalgia and the subsequent romanticized recollection of a persons environment – the where, how and why a nation and its people have come to experience the world. It is the written emotional essence of an era, recalling a convergence of cultures, leadership both social and political, and the otherwise mundane moments of a writer’s daily experience. These are the facets of life that echo within the written expression – in this way, and true to both the non-fiction/fiction genres (including mass media), a relationship is born between writer and reader (a participant within this unseen dialogue). A relationship of trust too that requires nourishment; the author is writing of his or her own experience insofar as it conforms, elaborates, or enlightens the reader toward a similar sensation or introduces them to a feeling previously unknown within their current station. For example, the media that appeared within Britain around the first decade(s) of the 20th century could not help but examine conflicts inherent to imperial control; embodied violently and visually in the dramas of the Anglo-Boer War, 1899 to 1902.

In his text, “Department of War and External Affairs: The Anglo-Boer War and Imperialism,” Jonathan Wild examines the dynamic relationship between reader, writer and editor that grew in influence around the beginning of the 20th century. More specifically, he recalls how the rise in sales and publication of daily newspapers became an important signifier to the various media outlets that the people were indeed listening: “A measure of the paper’s success can be gauged from the fact that during the Anglo-Boer War, the Daily Mail increased its circulation to over one million copies sold each day; these sales figures were unprecedented at this time for any equivalent publication in the world.”

This magnitude of readership was viewed by the political bodies of Britain as a necessary tool to both uphold public order and subsequently, shift the topics of discussion toward a direction in their favor. Thus, when writing about the wartime experience(s) of Londoners amidst this period of Boer violence, Wild suggests that various novelists would feature citizens reading papers – their heads down while walking and eyes glued to words on the page. This process of readership became akin to a hybridized form of “viewership” – thus, the sentiment of wartime was captured in ink.

The “philosophy” of reading can be related in a similar way to a modern experience of viewership. Nowadays everyone is connected via some form of social media and so the majority of information that we gather is interpreted from posts: Though singular, a post on social media may often be interpreting a piece of news or pop-culture, and so the majority of connected persons are saturated/surrounded or even flooded with information. Though that experience did not exist during the height of Empire and the totality of colonial happenings were to be displayed almost exclusively (with the exception of the wire-less or homes who as the century moved forward could afford a television) via the newspaper.

Reading itself became an image of civic participation, whereby the good Englishman, a student of Empire and state, would consistently engage in the events of his day. The government understood this phenomenon (as they too were participants) and although outright censorship was not commonly recommended, the omission of imperially damning incidents was frequent: A prominent example of this was the initial exclusion of prison camp policies during the Boer conflict from any news outlet. And although the majority of British military strategy would have remained “privileged/clandestine” information, the image of Boer-Anglo conflict as perpetuated by the media was one of imperial cultivation and civilization, with no mention of annihilation.

Further Viewing: Above is the first part of an expansive four part series covering the totality of British involvement in the Anglo-Boer conflict. It’s an older documentary from VHS re-recorded onto a digital platform (the audio quality is not perfect), though the voices and analysis of the war are very interesting.

Other(s): Preparing for the End of Colonial Rule

Racism & Oppression in India

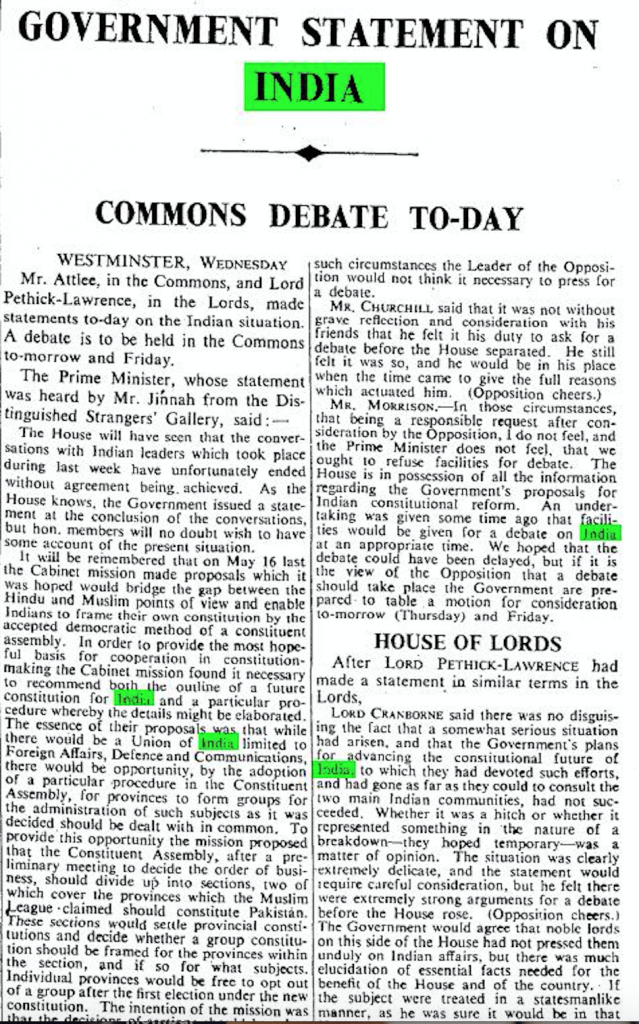

The below article details a meeting in Westminster, London (the center of Empire) wherein the English parliament and Prime Minister himself debated the departure of British forces from India alongside delegations from both India herself and the Muslim League. Their task was daunting – to orchestrate a reasonable system of governance that would assume control following the exit of British forces from the region. This meant not only that the Indian delegation would concede some regional command to the Muslim league, but also that the British would sign off on any plan-of-action. Religion and population became key factors within this debate – the nation’s two great religions of Hinduism and Islam were at odds, and had been for some time.

A member of the English cabinet had proposed the outlining of a new constitution in order to promote a more peaceable dialogue and cooperation between national parties. However, no lasting agreement(s) had been made and the majority of time likewise spent debating the allocation of Muslims into a region soon to become “Pakistan.”

There was no final say from the English at this point, and although a relinquishing of regional control would arrive by the following year, it was not so much British political savvy but rather the ability of Indian and Muslim delegations to arrive at common ground that inevitably lead to the formalization of “Home Rule.”

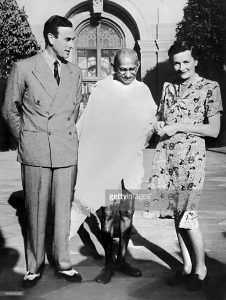

Yet, an article emerged within the The Times on April 29th, in 1947, stating: “The news of their presence [the Lord & Lady MB] spread like a fire through the crowd of perhaps 60,000 who rushed towards the over-bridge and gave Lord Mountbatten an enthusiastic ovation, shouting slogans like ‘Viceroy Zindabad’ or ‘Long life to the Viceroy.’” In this way and without hesitation, the British media were to champion the occasion as if it were the good graces of parliament that have allowed for a colonial people to attempt independence.

There was almost no mention of Gandhi or Mr. Jinnah. Furthermore any passing comment hailed the two facilitators simply as willing partners in a gracious concession by the Empire. The only sentiment aimed at positive political intuition from the Indian and Muslim delegations arrived via that same article as back-handed complement: Suggesting that India had been such a good student of empire and that the British were such exceptional propagators of leadership, that perhaps the nation was ready to strive toward independence.

The British therefore take full credit for their own departure, marketing it as a natural progression within the history of imperial formation and effectively absolving themselves of any blame when or if independence were to fail. There appeared to be no acknowledgement from parliament either as to whether or not such a feat could have been attained without the aid of Indian politicians.

A second article from this period echoes a near identical sentiment, affirming: ‘“Mr. Jinnah then made a brief reply [to Mountbatten] in which he asked that the thanks of Pakistan be conveyed to the King [of England] for his message of prosperity. He greatly appreciated the good will and sympathy which Britain had shown towards Pakistan.”’ Therefore, published in August of the same year and entitled “Power Handed Over In India,” this piece negates the position of Pakistan within independence to a that of a wholehearted recipient, and not a staunch proponent for egalitarian rights. There is so much passivity within this moment – whereupon the British savor the ceremony and occasion. Indians and future Pakistanis are marred, in contrast, and face a terrifying task ahead – the unification of a divided nation.

In this particular instance, however, “unification” more closely defines the inevitable process of partition: India and the new state of Pakistan disassembled themselves to be restored as two unique and self-governing societies in the years following. This was no simple process though as millions migrated across a nation while violence broke out along the way. Britain was able to deny any involvement or responsibility though, as they had already departed and were no longer culpable for the socio-political and theological disruptions then or of the previous decade(s).

Imperial Legacy and Nostalgia

When considering the many ways “Empire” has changed over the past century it is difficult to contend whether the Anglo-fervor that once drove a civilizing mission across the globe has really gone. The world of today is undoubtedly more aware of the downsides to the colonial experience than it had been years ago – a surge in revisionist histories took form around the 1970s and 1980s that strove to redefine many of the cultural experiences and voices often unheard. Along these lines the British imperial identity somewhat receded in the shadows of international policy – the divvying up of African countries in pursuit of diamonds and oil was no longer a public, political event.

Rather, the modern scars of Darwinian social thinking have found their place, or lack thereof, amidst the decedents of imperialists and their kin. For in an article entitled “Mutiny memorial trip sparks a new revolt,” via The Times on September 26, 2007, a perfect example of involuntary nostalgia can be found and examined through an imperial lens.

Specifically, the article details a group of British citizens – all descendent(s) of officials stationed and perhaps killed defending an English residency during the colonial period. Now on tour of the sites defended – a riot transpired in the modern day. The writer affirms: “Led by Rosie Llewellyn-Jones, a British historian… [the group] includes direct descendants of the generals Sir Henry Havelock, Sir Hugh Rose and Sir Henry Lawrence, who played significant roles in suppressing the mutiny.” When asked about whether the more or less aggressive Indian response had been warranted, however, Llewellyn-Jones affirmed her confusion on the matter.

There was some level of cultural consciousness from the British perspective: Planning to raise the Indian flag where the Union flag once stood and reciting from the Holy text of Sikhism in tribute of the fallen Sikh soldiers. Yet, it is markedly concerning that the touring group was so confused by the visceral response of the Indian people. It was if from the British imperial imagination the act of “granting independence” somehow equated to a full-pardon and forgiveness from the Indian nation for any and all past transgressions.

Accordingly, the touring group had likely seen themselves as acting in solidarity with the Indian people. They do have a shared ancestry though the context by which either group would characterize the position of the “other” is undoubtedly polarizing: Whereas the ancestors of British infantry and officers saw an opportunity to relive and honor the past, the Indian citizens surrounding this festival are calling for their admittance that what was done was not right! There is a tremendous burden of guilt that is rather willfully ignored by the touring persons.

Nostalgia for an imperial past is often shaped by romanticism. Therein an individual may go so far as celebrate the civilizing mission, idealize the conception of Anglo-supremacy, and call for a return to such times in the modern age. That being said, there is likewise a modern trend (without any hostility) that strives to recall an the “style of an era,” so to speak. An interesting modern example that softens some of the malice attributed to the British tour group’s pursuit of the past can be found in the below image:

Huckberry, a modern men’s clothing company that specializes in high-end men’s retail and outdoor clothing, affirms that the individual getting his hair cut is named Francis Richard Lee Mellersh, an accomplished RAF pilot and Vice-Marshall in the British Defense Staff. A quintessential Englishman, his father had also been a celebrated pilot during the First World War.

There is an obvious and understandable admiration for Mellersh’s style and so Huckberry has provided various links to websites or stores via an article from their page that strive to direct viewers to places where they too can acquire similar attire. The goal is simple: To appear classy and suave, as RAF airmen had during the glorious days gone. This romantic/nostalgic fervor defines a legacy of post-colonial engagement by people around the world. Indeed, Imperial nostalgia is not an exclusively British experience; and as the site contends, Mellersh’s style can be universally considered as top-class.

The danger, however, is when members of the former Empire carry this sentiment beyond their gentlemanly attire. For a phenomenon of recent days, more dangerous than touring groups and far less innocent than a redefining of the modern wardrobe, has seen a call a return to Empire itself.

The ethos of an imperial agenda has not been lost to Modern Britain: A clear shadow of the colonial endeavor has undoubtedly spurred forward the modern Brexit movement. Conversely, and perhaps the byproduct of education and time, there has equally been a rise in social awareness and criticism surrounding the British colonial endeavor across the globe. The world has grown tired of indifference toward the retelling of accurate historiography, and perhaps it is the rise in multi-media that has forged a sudden pressure to maintain accountability. Regardless, Britain’s colonial opponents (the majority of activists, socio-political educators, historians, former colonial members, etc.) have clearly drawn their line.

The millennial generation is perhaps the first to not know a Britain of some imperial means – as the last commonwealth states began to achieve independence in the 1970s and early 1980s. Britain has chosen to separate itself from the European Union (EU), the world must ask now whether isolationism can be seen as a precursor to “Empire 2.0.” What is the future of this former imperial power and where will its allegiance reside when no longer tied to Europe’s single market?

It is within a brilliant short story by George Orwell entitled, “Shooting an Elephant,” where the most poignant criticism of this Empire can be found. In which, Orwell suggests that the imperial imagination and the act of civilizing rule are two opposing phenomena: “That is invariably the case in the East; a story always sounds clear enough at a distance, but the nearer you get to the scene of events the vaguer it becomes.” Thus, it is impossible for those at the Empire’s center who have never seen the South African coast or cape, the great temples of India and her many villages, or a sunset over Pakistan’s legendary mountain range to consider what it truly and unequivocally means to be there. To be amongst the commonwealth and people: The British have provided the world with many wonderful attributes and the case can always be made that some positive attributes came from the occupation of foreign territory. Though, for the many Londoners never to really journey from “Cape Town to Cairo,” as their posters from the Tube would suggest, it seems aggressively nostalgic and oddly romantic to call for a return.

In this way, British Imperial propaganda has undoubtedly acted as a form of public history and contributed to the formation of various fictitious characters within the global vault of visual literacy and modern historiography. And for those who may not affirm the immediate affect of imperial rule within their (or their children’s lives) may only go so far as examine the many dailies, periodicals or features within news media of the day. In which they may likely come across many famous figures of literature – such as Gunga Dina, Tarzan, or Mowgli. Characters shaped by the imperial perception of a benevolent Britain living amidst the uncivilized other – such books have flourished on shelves or on screen. These figures too have permeated the ages. Thus, the most dangerous of all these colonial sentiments is not the elevation of the Empire over various subjugated states, but rather it is the emphasis of Anglo-British superiority (the essence of Darwinian social politics in purest form, the “Civilizing Mission”), as an imperial legacy and nostalgia unchecked have undeniably found their unspoken position within our society today.

“The world of 1906… was a stable and a civilized world in which the greatness and authority of Britain and her Empire seemed unassailable and invulnerably secure. In spite of our reverses in the Boer War it was assumed unquestioningly that we should always emerge ‘victorious, happy and glorious’ from any conflict. There were no doubts about the permanence of our ‘dominion over palm and pine,’ or of our title to it. Powerful, prosperous, peace-loving, with the seas all round us and the Royal Navy on the seas, the social, economic, international order seemed to our unseeing eyes as firmly fixed on earth as the signs of the Zodiac in the sky.”

An excerpt from Violet Bonham Carter’s, Winston Churchill: An Intimate Portrait

Works Cited

Ashling O’Connor. “Mutiny memorial trip sparks a new revolt.” Times [London, England] 26 Sept. 2007: 43. The Times Digital Archive. Web.

Chandrika Kaul, Communications, Media and the Imperia Experience: Britain and India in the Twentieth Century, (Scotland: Macmillan 2007)

David Gilbert and Felix Driver. “Capital and Empire: Geographies of Imperial London.” GeoJournal 51, no. ½ (2000)

George Orwell, Shooting an Elephant, (Monroe: 1936), 1-4.

Our Special Correspondent. “Power Handed Over In India.” Times [London, England] 15 Aug. 1947: 4. The Times Digital Archive. Web.

Our Special Correspondent. “Viceroy Welcomed By Crowd At Peshawar.” Times [London, England] 29 Apr. 1947: 4. The Times Digital Archive. Web.

Timothy Parson, The British Imperial Century, 1815-1914: A World History Perspective, (Oxford 1999).

Wild, Jonathon. “Department of War and External Affairs: The Anglo-Boer War and Imperialism.” In Literature of the 1900s: The Great Edwardian Emporium.

Images cited

“Waiting for the Queen” 1968. Eve Arnold G.B. Manchester, England

“The British Commonwealth of Nations,” http://www.gettyimages.com/detail/news-photo/the-british-commonwealth-of-nations-together-poster-news-photo/526779946#the-british-commonwealth-of-nations-together-poster-picture-id526779946

Poster from the London Underground, (1900): http://www.telegraph.co.uk/travel/destinations/europe/united-kingdom/england/london/galleries/London-Transport-Museums-alternative-Tube-maps/

Boers During the Anglo-Boer Conflict (1899): http://www.henrileriche.com/south-africa-anglo-boer-war-in-colour-suid-afrika-anglo-boere-oorlog-in-kleur/

“The Home Front” During WWII, http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/205070060

“A Newspaper Seller Outside Downing Street” (1929), Associated Press (AP): http://www.bbcamerica.com/anglophenia/2013/08/snapshot-21-photos-of-1920s-london/

Lord and Lady Mountbatten visit with Mr. Gandhi, http://www.gettyimages.co.uk/detail/news-photo/lord-louis-mountbatten-and-lady-edwina-mountbatten-receive-news-photo/146949342#lord-louis-mountbatten-and-lady-edwina-mountbatten-receive-political-picture-id146949342

“Partition,” https://www.thebetterindia.com/67924/unsung-heroes-partition-india-pakistan/

RAF pilot Francis Mellersh getting a hair cut: https://huckberry.com/journal/posts/iconic-style-raf-pilot-1942

A drawing by David Airey: 2016/2017, http://planet.mentalacrobatics.com/page/87/